- Instead of wasting water while excreting urea, their bodies recycle part of it. The nitrogen can be used to make amino acids, the building blocks of protein.

- Although they are warm-blooded, they still adjust their body temperature to the environment from about 37 to 40oC.

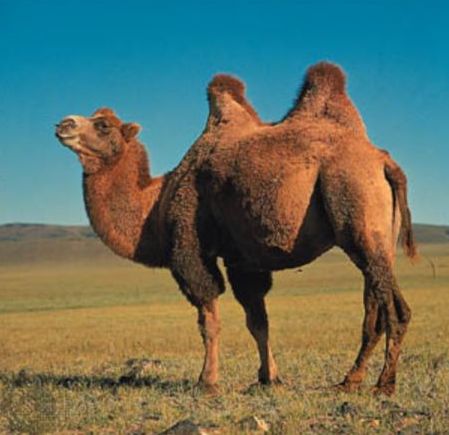

- Their fat is concentrated in their hump(s), so they have less insulation throughout the rest of the body. A camel does not store water in its hump(s) or in its stomach.

- Whereas the blood of most water-deprived mammals becomes thicker, leading to poor circulation and dangerously high body temperatures, a camel’s blood vessels retain most of their water. How was this discovered?

In the 1950’s, Knut Schmidt-Nielsen and his wife injected a harmless dye in to a camel’s bloodstream. They waited a while for the dye to distribute itself evenly. Then they took a blood sample and measured the concentration of the dye. Then the camel went 8 days without drinking in the desert heat. Although it lost a lot of weight (over 40 litres of water), the concentration of the dye in the blood revealed that the blood had only lost about 1 litre of water. In other words the rest of the water had been lost from tissues.

In the 1950’s, Knut Schmidt-Nielsen and his wife injected a harmless dye in to a camel’s bloodstream. They waited a while for the dye to distribute itself evenly. Then they took a blood sample and measured the concentration of the dye. Then the camel went 8 days without drinking in the desert heat. Although it lost a lot of weight (over 40 litres of water), the concentration of the dye in the blood revealed that the blood had only lost about 1 litre of water. In other words the rest of the water had been lost from tissues.

This is the kind of calculation that the Nielsens used:

Suppose that the original concentration of the dye had been 4.95 mg/L in 100 L* of blood. If the concentration of the dye had then increased to 5.00 mg/L, using C1V1 = C2V2,

4.95(100) = 5.00V2, would reveal V2 to be 99 L, a change of only 1 L.

But how did they know that the camel had a 100L of blood without killing it ? Let's say they had originally injected 8.0 mL of 6.19 g/L of dye. After even distribution of the dye(before the camel went 8 days without drinking), the concentration became diluted to 0.000495 g/L, thenC1V1 = C2V2,

(0.0080)(6.19) = 0.000495(0.008+V2), would reveal V2 to be about 100 L.

where

V2 is the volume of the camel's blood.Knut Schmidt-Nielsen who passed away three years ago(2008) wrote at the beginning of his memoirs:

"I has been said that schools impart enough facts to make children stop asking questions. Those with whom the schools don't succeed become scientists."

Reference:

Scientific American. The Physiology of the Camel. December, 1959.

Picture from George Holton, The National Audubon Society Collection/Photo Researchers